The Russian president has no challengers, but his failure to handle the Covid-19 and oil price crisis may have long-term implications for his rule.

Conspicuously absent during the first weeks of Russia’s Covid-19 outbreak, Vladimir Putin is back. Yet his televised interventions from behind a desk at his suburban presidential estate have been heavy on rhetoric and light on action, with day-to-day responsibilities left to others. Meanwhile, the economy is crumbling under the weight of low oil prices and a worsening epidemic. Even the prime minister has fallen ill.

For a president with no challengers, Putin has never looked so vulnerable.

It’s true that governments everywhere have struggled to cope with the pandemic. Moscow, though, is fighting three battles. First, like other nations it’s grappling with the direct medical and financial impact of a rapidly spreading virus. Second, it’s dealing with record-low crude oil prices, following a destructive spat with fellow producer Saudi Arabia that ended with a painful promise to cut output. Finally, it’s having to manage a popular vote on constitutional changes designed to keep Putin in power well past 2024, when his term ends. Balancing these three tasks appears too much even for a leader who portrays himself as a man of action.

Russia’s economy is sliding into its deepest recession since the end of the Soviet Union. It could, according to estimates from economist Sergei Guriev and others, contract by as much as 9% or 10% this year, far worse than during the 2009 financial crisis. A survey by Russia’s Higher School of Economics found that in March almost 60% of Russians said their income was unchanged. By April, it was barely a fifth. Unemployment is set to soar.

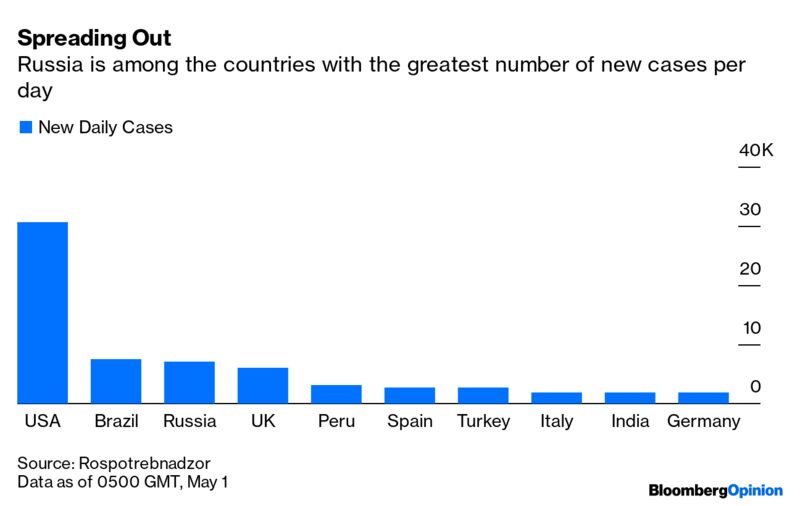

Management of the pandemic certainly isn’t going to plan, with Russia suffering more cases than China now. Coronavirus is showing up the threadbare state of the country’s health system, from faulty tests to a lack of beds. Changes to make the bloated post-Soviet system more efficient closed thousands of facilities, but not enough were reopened. Doctors and other medical staff are severely strained. The impact will be felt most as the virus spreads beyond wealthy Moscow.

It’s Putin’s biggest political crisis in two decades at the helm — in the very year he’d hoped to consolidate his mega-presidency with the vote to extend his term. The collision of Covid-19 and rock-bottom oil prices might have been an opportunity to show off the advantages of top-down, patriarchal governance. Instead, it has exposed a hollowed-out administrative structure.

Despite a $165 billion rainy-day fund, the state has remained on the financial sidelines, displaying a crushing lack of empathy for households and Russia’s six million small businesses. Some fiscal conservatism is understandable, given the unpredictable nature of the crisis, and the central bank has deployed monetary weaponry. Yet the government is relying on large corporations to not lay off their employees, and it has extended only paltry measures such as modest grants, tax deferrals and a derisory increase to unemployment benefits.

So far, according to the International Monetary Fund, the state’s financial rescue package amounts to some 2.8% of its gross domestic product, and even that includes plenty of loans and postponed payments. It’s a thin salve that won’t help the country recover. A group of prominent economistslast month reckoned support measures should be closer to 4.5 trillion rubles, or $60 billion, so 4% of GDP at least.

Significantly, Putin’s personal performance has been underwhelming. His spokesman had to dismiss rumors of a bunker hideaway. Always unwilling to get stuck into the nitty-gritty of governing, he has distanced himself more than usual from a crisis he seems unable to grasp.

He’s delegated responsibility to Moscow’s mayor, Sergei Sobyanin, to a cabinet led by the ailing Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, and to poorly equipped regional leaders. It’s an odd move after years of centralizing power and resources. While the president has returned to the public eye in recent days, he remains distant, notes Tatiana Stanovaya of R.Politik, a Russian political analysis firm. She says he looks like a man who’s grown unused to having to worry about popular support.

Before the outbreak, Putin’s ratings were already at their lowest point since before the annexation of Crimea in 2014, according to independent pollster Levada, and they appear to have worsened. State-funded VTsIOM, another polling agency, said last week that just 28% of Russians said Putin when asked to name a politician they trust.

Putin will no doubt hope to be seen as riding to Russia’s rescue. He can dole out cash eventually, while dismissing early mistakes as bungling by ministers and local officials. After two decades of concentrating power, however, it won’t be easy to deflect the blame — especially if Russia’s convalescence is long and painful and his spending promises come to little. His dacha self-isolation has echoes of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Crimean stay in 1991.

With few alternatives to Putin, the immediate risk for the leader is different this time. But there may be implications for his long-term ambitions. As Samuel Greene, director of the Russia Institute at King’s College London, points out, Russians are used to solving their own problems and have a largely symbolic relationship with the state, yet this is no normal crisis. Families were already dealing with shrinking disposable incomes, and they’re now at the limits of self-reliance. Moscow’s absence is felt more acutely than ever before.

The result is a political system that becomes ever more fragile. Institutions are eroded, apathy is rising and there is low trust in the presidency and government. An economic collapse will hurt even the elites.

Putin will, as usual, appeal to nationalism to tighten his grip — from the kerfuffle over the removal of a Red Army statue in Prague to delayedcelebrations to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. But his desire to hold onto power after 2024 will be dictated by his actions now.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net